Raising competent eaters: food neutrality

Finish your bowl of ice cream, then you can have some quinoa. If you behave yourself, you can have a fig. No more broccoli, you’ve had enough.

Sound ridiculous? Possibly. However, it is not unheard of to encourage eating based on expectations (what and how much should be consumed), and reward or bribe with “treat” foods. The examples flip the script on what foods are rewarded and which ones are pushed, illuminating the absurdity. A different approach, that does not override a child’s body cues, or generate food worry, is presenting foods in a neutral fashion.

What does a “neutral fashion” mean? It means no outside pressure, “eat your green beans, you’ll like them”, or placing higher value and limits on certain foods, “that’s enough mashed potatoes, eat more of your chicken.”

Why does this matter? As parents and guardians we are impressionable on our children. Connecting food to external cues can confuse intuitive eating. “Eat one more bite” dishonors a child’s satiety cues. “Try it!” threatens the joy of exploring new foods, creating rebellion and resistance. Praise for eating all the veggies, “you are such a good eater,” distorts the feeding relationship. Children start to eat to please vs stay in charge of their eating experience, and it messages food as either good or bad (food morality).

As a mom of two, I’ve committed myself, not perfectly, to presenting foods neutrally, knowing it is a key component to raising intuitive eaters. My personal experience and professional knowledge comes from leading child feeding experts, including Katja Rowell and Ellyn Satter. Here are a few of the lessons I’ve learned:

Drop the agenda. When my oldest started weaning, my registered dietitian brain kicked in and I started a food log. Yep, a baby food journal; I feared my son was not consuming his daily recommended intake. Instantly, mealtime became stressful, because I had an agenda, “he needs to eat his vegetables.” An agenda is the death of pleasurable meals and the perfect set-up for food fights.

Luckily, within a couple days I realized my lapse of judgment and we returned to a peaceful, pleasurable feeding experience, and my almost toddler, at the time, proved he knows what he needs. When I trust his internal wisdom to stay in charge he naturally consumes a well-balanced diet. There may be a day or two of minimal protein, then he request multiple servings of tofu in his miso soup or gobbles up handfuls of grilled steak and black beans.

Control tactics don’t work. They interfere with food acceptance. Pressure to eat a bite or try a new food is counterproductive. I’ve slipped, using less obvious control tactics, “try a bite, you might like it.” It may seem harmless, but as Ellyn Satter explains in her book Child of Mine, Feeding with Love and Good Sense, “children have within them the driving need to experiment with and master new food.” They want to grow up and don’t need to be pushed. Be patient, and they will get around to trying a variety of foods.

Multiple food exposures may be necessary. Trust your child to develop a healthy appreciation for a range of foods. This may require multiple exposures to a food. Remember the first time you tried dark chocolate or red wine? It takes time to acquire a taste for a new food. It can take 15 exposures before a food is accepted. For my oldest son, salad required years of exposure, without pressure, and patience on my part. Initially he looked at it then moved on to more familiar foods. A few more exposures, and he licked it while grimacing. There were multiple chewed bites that ended back on his plate. It was a slow process. Croutons ended up being the gateway to his love of salad with lots of ranch. As he develops, I suspect he will appreciate a wider range of salads.

Playing with food is a normal. It is a healthy part of eating. An introduction to octopus, video below, shows the common put it in your mouth and spit it out move. No judgement or pressure. Food exploration is a child-led experience when novel foods are offered. Children need the opportunity to explore new foods; it opens the door to new flavors and textures. Panic over wasted food or unconsumed food threatens this. Think back to a food you were forced to eat in childhood. Is it a food you love now? For me it was fried eggs every Saturday morning. I had to sit at the table until I finished them. To this day I won’t eat fried eggs in the morning; I’ll eat them at a different time of day or in a different form, e.g. scrambled, but not with my morning coffee.

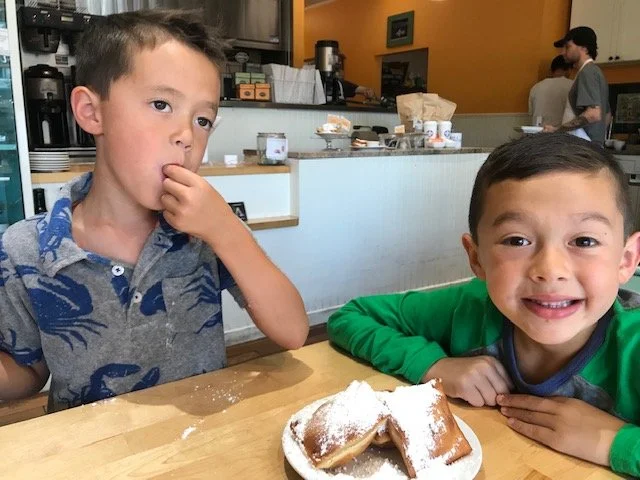

Dessert with dinner. The concept of including dessert with meals is a form of treating all foods equally. Earning rights to a sugary treat sets the message that dessert is something of higher value. Skeptical? From my experience, many people are. I shared the philosophy with some grandparents at a birthday party. They politely disapproved of the approach. Soon a huge corner of cake was set in front of my youngest, who at the time was only 3. He squealed with delight. Took two bites, and moved on to the birthday activities. The intrigued grandparents gave each other a surprised look. For my son dessert is not restricted. He knows enjoyable food will be made available again. This allows him to relax around food and honor his satiety cues (hunger/fullness).

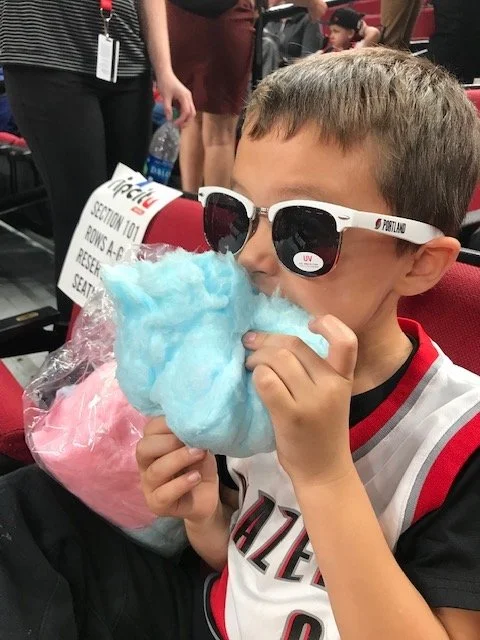

No “good” or “bad” foods. My boys ask for extra servings of ice cream on occasion, and have been known to eat only their chips and fruit at lunch. I’ve opted not to make an issue of these moments. As I explained in drop the agenda, they comes back around to eating nutrient-rich foods. I’m a huge advocate for not labeling foods “good” or “bad.” As a private practice dietitian, adult clients regularly share the guilt and shame associated with eating a “bad” food. The thinking intensifies food worry and unnecessary guilt (remember, food does not have a moral compass). This type of black-or-white thinking harms their relationship with food. Not surprising, restricting “bad” foods prompts a preoccupation with the food item, generally resulting in overconsumption when the regulated food is available, i.e. going to a friend’s house or eating in secret.